Source: Joel Muniz on Unsplash, June 25, 2020.

By: Bailey Perkins and Melanie Figueroa Zavala

Our Approach

Our interdisciplinary approach analyzes the health data and social inequities illustrated throughout Idaho Counties. Bailey’s areas of study integrate biology to explore the physiological impacts of diet and disease, psychology to investigate mental health challenges associated with food insecurity, and writing in leadership to translate scientific data into more accessible information. Melanie focused on the structural inequities using critical theory, environmental studies to access resource distribution, and Spanish language skills to bridge communication gaps in diverse communities. By utilizing these six areas of study, we emphasize the importance of a holistic and inclusive strategy to improve public health and food equity in Idaho.

What is Food Insecurity?

Food insecurity involves the lack of access to food consistency needed to engage in an active and healthy life. “Food insecurity is a complex phenomenon encompassing food availability, affordability,…cultural norms…[of] acceptable means of acquiring food, and individual food utilization”. (Jones, Andrew D. 2017). Factors influencing food insecurity may include poverty, unemployment, systemic inequalities, and barriers to accessing public assistance programs like SNAP. Adolescents facing food insecurity in the U.S. are more prone to conditions like metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) due to reliance on ultra-processed, low-cost diets. Through understanding these underlying causes that lead to food insecurity, we can begin to address this issue as a consequence of systemic challenges.

These systemic challenges can be better understood through a critical lens that analyzes social and policy systems that lead to disparity in food access and affordability. This analysis highlights the relationship between health and access to healthcare; food insecurity is a result of failing systems that prioritize capital over the well-being of communities. As an example, the farmworking community is particularly more vulnerable to economic exploitation, rural isolation, physically demanding labor, and elevated risks of hypertension and diabetes. These overlapping challenges contribute to and are escalated by food insecurity, creating a cycle that severely impacts the health and well-being of all community members.

In terms of health and access to healthcare, food insecurity is a result of failing systems that prioritize capital over the well-being of communities. Horton’s book They Leave Their Kidneys in the Fields (2016) discusses the exploitative realities of farmworkers, focusing on the social factors that lead to their higher rates of diabetes and hypertension. Horton introduces the concept of a syndemic as a cluster of conditions that interact biologically and socially (p. 124). We define syndemic as the evolution and relationship between social and health conditions. Food insecurity works within a syndemic. The social factors of income and food affordability interact with the malnutrition and health complications resulting from this reality. This highlights the danger of food insecurity and the importance of addressing it within our communities.

Farmworkers are the backbone of our nation’s food supply. Unfortunately, many struggle to put food on their own tables. This highlights a broader issue, entire communities, including those here in Idaho, are deeply affected by food insecurity. Recognizing this, we focused on examining and identifying data on the unique vulnerabilities that face our communities with a goal. To better understand this pressing issue.

Idaho Data

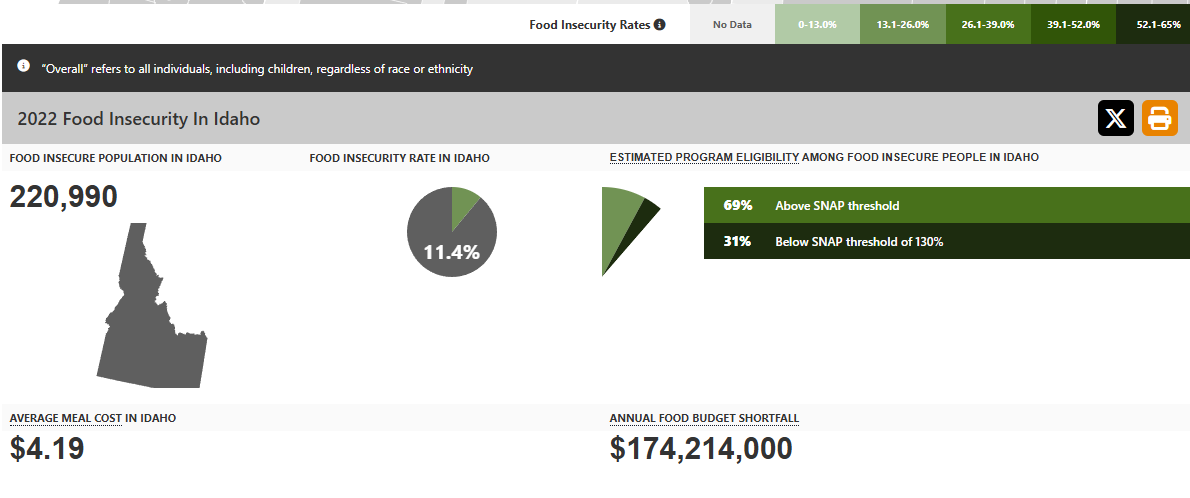

The data presented through County Health and Rankings & Roadmaps and the food insecurity map of Idaho from Feeding America allow us to have detailed data for each county.

Idaho Counties with High Food Insecurity:

- Canyon County: 19,000 individuals face food insecurity.

- Kootenai County: 14,580 individuals are food insecure.

- Ada County: 33,460 individuals struggle with food insecurity.

Idaho Counties with Limited Access to Healthy Foods:

- Canyon County: 14,041 individuals have limited access to healthy foods.

- Bonneville County: 11,887 individuals experience limited access.

- Kootenai County: 10,102 individuals face barriers to accessing healthy foods.

Counties with higher food insecurity also showed results of yielding higher percentages for diabetes and obesity populations.

Interventions are needed for both urban and rural areas

Implications of Food Insecurity

Health Implications:

Your health is interconnected and should be viewed as a holistic approach

- Physical Health: Food insecurity is linked to malnutrition, obesity (due to reliance on cheap, calorie-dense but nutrient-poor foods), chronic diseases like diabetes, and metabolic issues such as MASLD.

- Mental Health: Food insecurity increases stress, anxiety, depression, and feelings of shame which can lead to isolation.

- Child Development: In children, we could see stunted growth, developmental delays, and poor academic performance.

With food insecurity at about 16.9% for all households and 22.5% for households with children in 2013 (Gundersen, C. et al. 2015), It is necessary that healthcare professionals are aware of the negative health outcomes associated with food insecurity. Associated risks with food insecurity in children include birth defects, anemia, lowered nutrition intake, cognitive problems, and aggression and anxiety. In older adults, you can expect lower nutrient intakes, poor to fair health, and depression. Non-senior adults’ negative health outcomes also include decreased nutrient intake, mental health problems, depression, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and poor sleep. Awareness of these symptoms and a survey to determine food insecurity, since every person may define food insecurity differently, healthcare professionals could help individuals better access programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Source: Trends in exhibit 1 illustrate food insecurity within the United States. This analysis takes place from the years 2001-2013, which includes the Great Recession of 2007-2009, which explains the increase in food insecurity during these years. The percentage of those who are food insecure still remains high and has not decreased to rates previous to the recession. Through this graph, we can also analyze the percentage rates of all households, beginning at an estimated 11% from 2001-2007, then rising to 16.9%. Households with children experienced food insecurity rates from 18% from 2001-2007 to 22.5% in 2013.

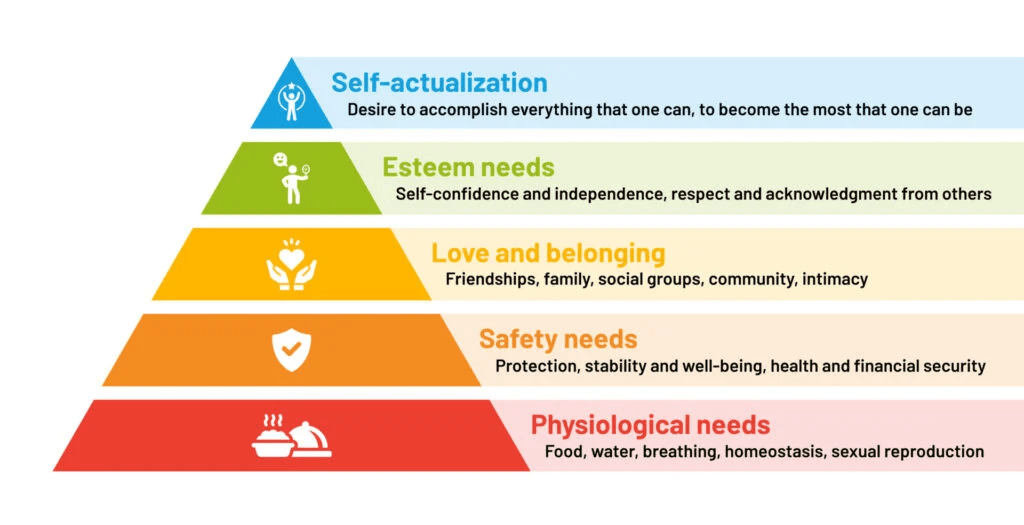

Through a self-reported assessment of mental health status in relation to food insecurity across 149 countries, it was concluded that across all assessed regions, food insecurity continued to correlate with poor mental health. Having uncertainty over where your next meal would be sourced provoked a stress response that contributed to anxiety and depression. Referring to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, having access to food and water is the primary necessity of survival which includes psychological and physiological needs. The secondary necessity mentioned is having secure access to these resources. Without these needs, individuals face setbacks towards accomplishments. The study explained that “individuals may resort to acquiring food in socially unacceptable ways as a coping strategy” (Jones, Andrew D. 2017). Eliminating food insecurity would establish an equal foundation for all.

Source: Simply Psychology, by Saul McLeod, PhD, 2024

Socioeconomic Implications:

It is a result of socioeconomic systems that contribute to the formation of food deserts and “food segregation.” These terms refer to the ways in which low-income communities, particularly those of marginalized racial or ethnic groups, lack access to affordable, nutritious food. This happens due to historical and ongoing discriminatory urban planning and economic development practices. Wealth disparities limit food security because impoverished individuals may prioritize other survival needs, such as housing or healthcare, over nutritious food. The CDC uses the example of the impact of diabetes on food insecurity in the Hispanic population to speak to the concerns of unaffordable medication and the implications this has on nutrition–creating a cycle of oppression that leaves these populations vulnerable to poor eating habits and more health complications as a result.

Food is treated primarily as a commodity rather than a basic human right. This commodification often leads to unequal distribution, where food availability depends on purchasing power rather than need. Hochedez 2022 discusses the ways in which our current food systems reflect the capitalistic global economy and how this disenfranchises our most vulnerable populations. She states, “Rapidly rising food prices reflect the interdependencies between stakeholders and spaces in food systems, their globalized structure, relationships of domination, and the power of middlemen (large-scale distribution, stock exchanges, etc.). These trends have repercussions on every level, especially for the most precarious populations for whom it is even more difficult to feed themselves properly.” On a global scale, these disparities are exacerbated. The overproduction of resource-heavy foods (e.g., meat and dairy) for wealthier populations exacerbates land use changes, deforestation, and greenhouse gas emissions. Similarly, high levels of food waste, especially in affluent countries, contribute to inefficient resource use while hunger persists in other regions. While export-oriented agriculture in developing countries often prioritizes cash crops over local food needs, perpetuating food insecurity.

Preventing Food Insecurity

In order to prevent food insecurity and the disparities in the food distribution system, it is necessary to recognize food as a human right. Implementation of policies that ensure universal access is vital. A restructuring of the global food system is needed to ensure that sustainability, equity, and local food sovereignty are a priority.

- Federal Programs: SNAP and school meal programs.

- Local Initiatives: Food banks, community gardens, and non-profits addressing hunger.

Support organizations that are fighting food insecurity in Idaho and advocate for universal food access

Donate, volunteer, or partner with organizations addressing food insecurity:

Provides emergency food assistance across the state.

Works on local relief initiatives for food and resource distribution.

Boise Kitchen Collective (@boisekitchencollective on Instagram):

Focuses on equitable and community-driven food access.

A Boise-based initiative creating sustainable food systems for underserved populations.

Food Pantries In Boise:

Find your nearest food pantry and donate resources and time

Advocate for Policy Change

- Push for local and state policies that promote equitable food distribution, such as food subsidies for low-income families and investments in urban farming and food sovereignty projects.

- Support efforts to include language-inclusive access to assistance programs for immigrant and refugee communities.

Addressing food insecurity requires an interdisciplinary approach that highlights health, social equity, and resource distribution. Our approach- utilizing biology, psychology, writing in leadership, critical theory, Spanish studies, and environmental studies- we were able to better understand the root causes and the critical impacts of food insecurity. In Idaho, the large number of individuals facing limited access to healthy foods and food insecurity is cause for concern and highlights the urgent need for intervention that includes expanding federal programs like SNAP and prioritizing community-driven solutions.

Food is a fundamental human right and a basic necessity for survival, and achieving food equity demands collaboration. Advocating for policy changes, fostering sustainable food systems, and ensuring that everyone, regardless of socioeconomic status or cultural background, has access to nutrient-dense and affordable meals. Together, we can build a future where the rates of food-insecure individuals drop to zero, leveling the playing field and building healthier and more resilient communities across Idaho and beyond.

Resources:

Pass, Will. “Food Insecurity Increases Risk for Adolescent MASLD.” MDedge: GI & Hepatology News, 4 Dec. 2023, https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/266852/liver-disease/food-insecurity-increases-risk-adolescent-masld.

Jones, Andrew D. “Food Insecurity and Mental Health Status: A Global Analysis of 149 Countries.” American Journal of Preventative Medicine, Science Direct, Aug. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.008

Gundersen, Craig, and James P. Ziliak. “Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes.” Health Affairs, vol. 34, no. 11, 2015, pp. 1830–1839. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645.

CDC. “La diabetes y la inseguridad alimentaria | Diabetes.” Diabetes, 30 April 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/es/healthy-eating/la-inseguridad-alimentaria.html. Accessed 10 December 2024.

Horton, Sarah Bronwen. They Leave Their Kidneys in the Fields: Illness, Injury, and Illegality Among U.S. Farmworkers. University of California Press, 2016. Accessed 10 December 2024.

Hochedez, Camille. “Food Justice: Processes, Practices and Perspectives.” Review of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Studies, vol. 103, no. 4, 2022, pp. 305-320. ProQuest, https://libproxy.boisestate.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/food-justice-processes-practices-perspectives/docview/2932254869/se-2, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s41130-023-00188-4.

McLeod, Saul. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.” Simply Psychology, 24 Jan. 2024, https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html.

Leave a comment